I consider myself a historical wargamer and when this debate about realism crops up on forums and social media, as it regularly does, I'm always interested to read how people respond.

I've often heard it said that wargaming can never be realistic - no one is in danger, real bullets are not flying and there is no blood and gore. Well, all I can say is, thank goodness. That's certainly not the realism I'm looking for in my games.

Much comes from how we interpret or use the term 'realistic'. If the rules I am using give a powerful anti-tank gun a high chance of disabling a tank with weak armour, you could argue, those rules offer a realistic outcome. As gamers we resolve this action with the roll of dice and we may mark the destroyed tank with imitation smoke or something similar.

Is that realistic? Well, clearly it isn't. There is nothing in the action of rolling dice and placing markers that in any way resembles the impact of an armour piercing round on an armoured vehicle and its occupants. So, while the rules accurately reflect the likelihood of the anti-tank round damaging the tank and produces a plausible outcome that aligns with our reading of actual events, the process by which we replicate that on the table in miniature is anything but realistic.

So, if it's not real, what do we mean when we say a game is, or isn't, realistic? To a great extent that depends on what part of our games we are applying the requirement for ‘realism’. I think much of that boils down to the role that the rules assign to the player. In nearly all cases players are put in the position of command, be it the corporal of an infantry section, or the general of an army. The question I would ask is, how accurately does the game portray that role and the subordinate roles undertaken by the model figures on the table? For many the answer lies in the outcomes. We want a plausible result from a particular event. The process by which we get there - be it consulting charts, rolling dice or drawing cards from a deck are just the game mechanics to help us reach that outcome.

Perhaps then, I'm not looking for realism, what I am looking for is accuracy. I'm inclined to think that can be a more useful term to use when referring to rules that have some claim to being based on historical events.

People look for different things from their gaming experience and we each settle on what works best for us. Those gamers who are looking to model certain aspects of history on the table top will come at this from several different angles. Much depends on their reading of history and what they believe are the key factors that determine the outcome of combat. Some want the emphasis to be on command, others would prefer to concentrate on the effects of weapons systems, while others want more focus on the morale of the soldiers behind the weapons. Unsurprisingly, there are those that want a balance of everything.

Needless to say, there are some who regard this whole discussion as futile. They argue, there is no point even pretending a wargame bears any resemblance to reality, it is entirely abstract and we kid ourselves if we think otherwise. It's no more than pushing around toy soldiers, rolling dice and having a laugh.Philip Sabin in his book Simulating War gives a good overview of moments when this has been the case and it's worth quoting at some length:

In the years before 1914, wargaming helped to persuade the British that a continental commitment was needed to safeguard France against outflanking through Belgium, and it also helped the Germans to devise just such a move in the form of the Schlieffen plan. Wargames showed both Germans and Russians the potential vulnerability of a two-pronged assault on East Prussia to defeat in detail, but it was the Germans who took this lesson to heart and applied it at Tannenberg.The decisions the military wargamers are making will only be of use if they reflect accurately the processes by which commands are given and acted upon in the real world. In other words the rules of their games need to be realistic if they are to offer any useful lessons.

While the military have a very obvious reason to want their games to be realistic, the claims by publishers of rules for the hobby would indicate this is something that they also aspire to. Warlord Games claim that Bolt Action "puts YOU in command of the most famous and brutal battles of the Second World War" while Battlefront Miniatures state that their Flames of War rules "allow you to refight the enormously varied battles fought around the world from 1939 to 1945." MMP, the publishers of the board game Advanced Squad Leader, claim their rules "..allow you to simulate practically any tactical-level engagement of World War II".

If, in theory at least, a wargame can reflect accurately actions taken in the real world, why do we find ourselves discussing if, or how, a particular set of rules is realistic or not?

I think this is because rules writing for tabletop games is a creative and subjective enterprise. The writer's challenge is to create a playable game based on their understanding of a particular period of history. In the interests of playability there are compromises and abstractions to be made, but it doesn't follow that accuracy has to be jettisoned. Simple doesn't have to equate with unrealistic. This is where the creative aspect of rules design becomes particularly significant.

We can apply this thinking just as easily to wargame rules. If we take as an example a period of history where all commands were by voice or messenger, then a set of rules wanting to accurately represent the period needs a mechanism to reflect the issues all commanders faced in communicating with their subordinates. We can approach that in several ways, depending on the level at which we want the players to make decisions.

Let's take the case of a message carried by a runner. If the player is taking the role of the senior commander their key concern is that the message reaches the intended recipient and is acted upon in a timely manner. It is the outcome, not the journey, that is important. If that's the case, we don't need to follow in detail the variable speeds at which the messenger might travel, understand the obstacles they may confront, or the death or injury that may result. That might be quite appropriate for a game set at the level of the messenger, but not necessary if the player's role is that of the commander. We only need to know if the message was received and understood by the recipient.

Much like the example of the fire drill, if experience or history tells us say that 1 in 3 of all messengers failed to deliver their message, then looking at this solely from the commander's perspective we could resolve the outcome by rolling a D6, where a roll of 1 or 2 tells us the message failed to make it through. While this single roll of a dice could be considered accurate in terms of reflecting the chance the message is received it is an abstraction in terms of game design, however that doesn't make it invalid as a reflection of reality. What would be inaccurate or unrealistic would be to have a game mechanic whereby the commander can communicate across the battlefield without the need to send a message, or one that assumes that every message arrives at its destination with perfect timing, to be understood and acted upon exactly as you the commander wished. It strikes me that would be far less realistic than the roll of a D6 to determine the outcome.

Like writing history, every rules writer has a distinct view of where the importance lies. Is it the weapons themselves or is it more about the soldiers behind them? Is firepower the most critical factor or is morale more important? What about leadership? Are battles won because of great generals or is that determined more by the training and discipline of the troops under their command? Military historians and theorists cannot always agree, so little surprise that rules writers come at this from different perspectives.

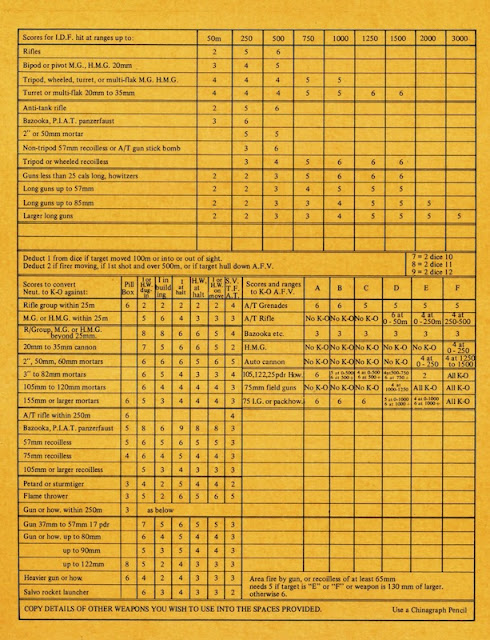

In the 1970s and 80s many wargame rules focussed on the impact of weapons. I’m certain that at the time it had a lot to do with trying to elevate the perception of miniature gaming above simply ‘playing with toy soldiers’. Much time, energy and research was focussed on producing charts and tables to reflect the likelihood of weapons hitting at various ranges and the damage they might inflict should they strike their target. Debates about realism often centred on these aspects and rules that failed to factor in the varying attributes of different weapons to the player’s satisfaction were often regarded as unrealistic.

Yet it is much easier to assign a degree of accuracy to mechanical factors because they can be measured and verified. We know the maximum speeds of most vehicles, there is copious data demonstrating the penetrative power of armour piercing rounds on different thicknesses of armour, we know the time it takes a trained soldier to load a smooth bore musket. Armed with this sort of data we can create a set of rules that deliver reasonably accurate outcomes for these activities.

What is much harder to measure and assess is human activity which introduces more unreliable and complex sets of actions. While we can calculate the likelihood of an AP round piercing a tank's armour it is much harder to put a fixed response to the way the crew will react to being shot at by such a powerful weapon. Other more variable factors come into play like bravery, experience, training and fear. What we do know is that the response is likely to differ, with a myriad of factors coming into play at any one time. In fact the one thing we probably know for sure is that the response won't be mechanical, it is far more likely to be emotional. In other words we can't predict with certainty what the reaction will be other than to say it will vary with individuals and in different ways at different times. While it won't be entirely random it will be harder to predict. I think most of us would agree that to assign an identical response by all humans in response to a similar event is unrealistic.

A set of wargame rules that treats the soldiers on the table like robots is far less likely to reflect accurately the response of humans to the situations they might face than one that factors in a more variable response to a wide range of events and circumstances. Soldiers told to advance across an open field towards buildings known to occupy the enemy are likely to respond in different ways. Inexperienced troops may not show enough caution and advance recklessly, yet they could also show excessive fear and barely move at all. Hardened veterans may not display the recklessness that comes with inexperience but they may show the caution that comes with experience. The challenge for a commander is managing a response to all these variables and not least being unsurprised when they do occur.

Can that be reflected on the table top with any accuracy? Again it depends on the level of abstraction as much as your reading of history and psychology, but I would think to not do so at all would be the most unrealistic response.

So, while a wargame can never recreate the reality of actual warfare on a table top, it is possible to try to reflect more accurately the outcomes of decisions that are made on the battlefield. Yet it doesn't follow that a realistic or accurate set of wargame rules must be an overly complex simulation. The skill and art of the rules writer is to distil the key elements down into abstractions that make them straightforward game mechanics. If successful then they give the commander - you, the player - a much better feel for the decisions and issues faced by your historical counterpart.

If it is at all possible to say that historical wargames can be realistic it must then beg a different question to the one I started with, which is, what is it that can make a set of rules that claim to be historical unrealistic?

Very nice presentation of both "realism" and "accuracy ". I am sure that I will reread this essay several more times.

ReplyDeleteInteresting article, some food for thought there. To answer the begged question at the end, I guess for a wargame to be unrealistic it must have some combination of units/combinations of units being available to the wargamer that wouldn't have been available to real commanders, and units behaving in ways that the real-life counterparts wouldn't have done.

ReplyDeleteI think all games, whether wargames or not, beat to the same drum. Pieces generally have a movement rate, an attack value and a defensive value and when thought about, that can be applied to most things, even family games such as Ludo and Monopoly - so it is actually the ‘dressing’ that makes our games what they actually are.

ReplyDeleteI am a wargamer of old and I travelled the journey from first getting my Airfix figures off the floor and onto the family dining table through to having umpteen rulebooks on every period, nice battlefields and nicely painted figures, trying to be accurate.

But the longer I do this thing, the more I am going full circle and wanting to travel back to my younger years when wargaming was a voyage of discovery and more ‘fun’ than it is today. So I am becoming increasingly happier seeing my games more as thematic than rigidly accurate.

However, having said that, there are some things that I can’t go with. I can’t remember the rules, either Bolt Action or Flames of War, but they allow Katyuska (sp?) rockets on the table in what is essentially a tactical game and yet the rockets should be firing from a distance of 5000 yards plus, so that can’t be right … can it :-).

For me, an increasingly important element of a game is giving the player the right emotional response, putting them in the hot seat of the actual commander. So if playing Hastings, the Norman player should be feeling the shear frustration at the grind of trying to get up that hill and trying to break into Harold’s position as the clock ticks, while Harold should be desperately plugging every gap and feel that he is just holding on by the skin of his teeth.

At Waterloo, playing in the area of Hougoumont, the French player should be frustrated at the delays caused in taking the complex and the fact that they are just feeding more and more men into that cauldron. The Anglo-Allied player should be pretty much on their knees, holding out grimly, just hoping to get through the next turn.

If the game can impart these sort of emotional reactions, then regardless of their detail, complexity or method of system, they are in fact delivering the right sense of battle.

The early rule writers were generally men with military experience and their rules tried to reflect an exactitude of accuracy that falls out from that. The modern sets go for a more intuitive feel, but both have the same goal.

I know the poster has a passion for original Squad Leader by Avalon Hill, if we look at that, accuracy plays second place to ‘feel’ (described in the game as abstraction) and my goodness, it has ‘feel’ oozing out of every quarter and did set an entire generation of us on the course of a life long passion for WWII tactical games.

In my view, I do though want my rules to sit within boundaries, such as how effective should the napoleonic cavalry charge be against a square or the initial impact of a celt charge against the Roman line v’s Roman discipline getting the advantage in later turns once the initial impetus of charge is lost or what effect did 80mm mortars have on armour and are we looking at both physical and mental when when our systems reflect that and what are the known chances of a torpedo being accurate.

But outside some of these very obvious parameters of ‘accuracy’ I know my tabletop action is just a game and increasingly, I am at peace with that (again!).

A very good post and one which certainly gets the old grey matter ticking over. Realism for me has to also cover good command and control benefits and hindrances that, at the very least, historically their army should have. Though I have friends who dislike being handcuffed by Napoleonic Austrian command constraints , I’ve never had an issue playing an Archduke or two😉

ReplyDeleteA good question, well asked. Where to start? Perhaps to note that the most important element in wargame design, both for the hobby and, most definitely, for the military professional is to define what you want from it i.e., 'requirements capture' (in my experience, where many failed projects went wrong). If (big if?) you can define the question you want addressed, or experience you are seeking, and stay focused on that, and stay away from unnecessary* detail, you are well on the way. [*you need to be sure these assumptions are valid] Because of this it may be acceptable for a wargame to treat some matters in an unrealistic fashion for various reasons, resource (e.g. the courier is assumed to always get through as on some days may be the case) yet still be a valid wargame. If it's a historical game, and on the day all couriers did get through, is it realistic to make it that way, or unrealistic to not allow for what might have happened? The answer goes back to what you wanted your game to be about.

ReplyDeleteSo, getting back to your question, what makes a rule-set 'unrealistic', it's really down to either violating the laws of physics (e.g. troops can't instantaneously materialise thousands of miles away - unless it's a sci-fi game) or, far more likely, they run counter to the players prejudices (using the word in the non-perjorative sense).

I think I like CoC because it set at such a low-level that the outcome could so easily be flipped by the presence of a slight, almost imperceptible, fold in the ground. Clearly, this level of detail is ungameable and in reality often an unknown until encountered. Similarly, the 'uncertainty' created by the way troops are brought into the game forces the player to make decisions based on limited information (I like this in a game). This last point is a key element in the use of games by people like Professor Sabin mainly as educational and training tools to get players accustomed to making decisions with limited information.

I think I better stop...

I can think of a couple of examples of 'unrealistic' rules. The first was a computer game of Waterloo which allowed cavalry to take garrisoned villages by storm as a matter of course. The second was a set of 'Age of Sail' rules that ignored the wind strength and direction. Both failed to take account of some of the basic facts of the conflicts being represented. These errors can be - and usually are covered in other games.

ReplyDeleteOther fundamental issues - let's take the 'helicopter view' as an example - are very difficult to eliminate in a game where the spectacle of figures on the table is important.

A nicely-argued and thoughtful piece. For me, there is a three-way tussle in any set of rules between playability, complexity and the feel of reality and to get some kind of balance between the three is almost impossible. Therefore, there are trade-offs to delver the ideal outcome, which to my mind is a game with a strong narrative element that gives the players a sense of it feeling right for the period. Also, for me, I want a game where every choice and decision made is subject to uncertainty. I don't want a godlike gaze, I don't want predictable outcomes and I do want to feel frustrated when things go wrong (TGW) for apparently random reasons. The TGW principle is key to the development of a narrative. If something doesn't come off, so be it. Try something else. That is where the fun lies.

ReplyDeleteJoe Morchauser in the forward to his 1962 book, How to Play Wargames in Miniature said “Someone, somewhere, at some time, has thought of every rule, and every exception to every rule, and every exception to the exception." Perhaps, then, all new rule sets do is rewrite the order or use of rules already used somewhere, Certainly Pessimistic! I think that several rules sets written since that time prove the misconception of that quote. Two come to mind; Cross Fire by Art Conliffe and Chain of Command by Too Fat Lardies. I am sure there are others with which readers will enlighten me..

ReplyDeleteVery good essay, full of good reflections.

ReplyDeleteI think in terms of the level of abstraction and detail how far the rules should go will depend on the command level of the game. A squad level tactical game demands more technical detail from the weapons rules. At a higher level, regiment, brigade, division or army, the detail is less as the actual results statistic replaces the detailed shot-by-shot result. It must then be taken into account that commanding a platoon requires a shot-to-shot dispute, while commanding a division requires a broader vision of the general results of the operation. In other words, higher levels of leadership force you to put aside the fight of each individual soldier, leaving it to a good reception of statistics by the rules, in order to command the entire force. And this is not in the rules, it must be in the mind of the player.

It's just a contribution. Thank you so much

(As originally posted on TMP) I tried to stay out of this but in the end I couldn't – the topic is too interesting. Thanks, TacticalPainter! Nice essay.

ReplyDeleteFor me, the key is in one of your closing sentences: "it is possible to try to reflect more accurately the outcomes of decisions that are made on the battlefield". I'm with FlyXWIre who said on TMP that it's all about decision-making.

When I'm playing, I want to be faced with new and challenging decisions every turn. When I design a scenario or run a game, I want it to confront the players with similar decisions (strategic / tactical) to those that the historical generals would have had to make.

If the game rewards good plans or decisions and punishes bad ones in what Bobm described on TMP as a 'convincing' way, then that's the degree of realism I'm looking for.

Not everyone wants that. In my own series of "Reflections on Wargaming" essays, there is one called "Wargames: how much 'war', how much 'game'?"

https://bloodybigbattles.blogspot.com/2015/11/wargames-how-much-war-how-much-game.html

My own answer to the question originally posed: yes, of course they can. Not in every respect, but in terms of the particular phenomena they aspire to model, the modelling can be more or less realistic and sufficiently so to achieve whatever the aim of the game may be.

Thanks again for a thought-provoking essay and well done for generating so much discussion!

Great post!

ReplyDeleteI'll give you a couple quotes from James Dunnigan's The Complete Wargames Handbook that have always guided my thinking in this area:

"To be a wargame, in our sense of the word, the game must be realistic. And in some cases, they are extemely realistic, realistic to the point where some of the wargames are actually used for professional purposes."

"A major limitation of a wargame is that it appears to be a very accurate representation of an actual conflict. The problem is that while the games are somewhat accurate, they are quite inaccurate in certain important ways in order to make them playable."

This is from a 45 year old book on wargames. The bottom line for me is that to be a wargame, a game must be "realistic" in some respect, such that that players can either learn about the subject matter of the game or apply the lessons of history in the play of the game. But no game, whether a highly complex computer-based simulator or a highly abstract miniatures or cardboard tabletop game, can be realstic in all respects, because ultimately they must be playable.

Players who prefer games that have leaned more heavily into playability may decry that a game is in any way realistic. And players who prefer something more "crunchy" or that is leaning more in the simulation/realism direction may complain that the former's game is "too unrealistic." These are preferences about what is a necessary tradeoff between playability and an attempt to reflect reality/history.

Your use of the word 'plausibility' coincided most with my own thoughts. I think that's about the best we can hope for from recreational miniature wargaming. The kind of wargaming done in professional military circles is a very different thing and shouldn't be confused with our amateur efforts played for enjoyment.

ReplyDeleteI don’t think it’s possible to draw a clear distinctions between recreational or amateur gaming and professional gaming.I know an Irish Army commander who uses Osprey’s Undaunted Normandy as one of many training tools. Phil Sabin’s book is all about how he used ‘recreational’ wargame mechanics to design playable 2 hour games for student officers in military academies. None are detailed simulations they are ways of encouraging ways of thinking and problem solving but also with plausible outcomes and processes. They are all games that a recreational gamer could play (and enjoy). I know other wargames are very different, but that’s my point, it’s a very broad scale of game types and the games played reflect the players viewpoint. It’s why we sometimes find it difficult to find the right sort of opponent. I think your own thoughts are just like mine, they are just our opinions, there is no single answer to my initial question.

DeleteTo me, realism is the end result of a process. Terms like accuracy and plausibility are certainly considerations, but IMO it has to start with authenticity - a desire to reflect outcomes as they should be. So that what happens seems and feels "right" to us.

ReplyDeleteSo the game mechanics themselves simply need to provide the means to properly reflect those outcomes. The "how" doesn't matter so much as the "what", in the end.

As you mentioned, the best game designers find the most elegant, simplest, and most intuitive ways to design the mechanics. Authentic outcomes don't necessarily require complex rule systems, any more than good poetry requires hundreds of words.

In fact, when the rules are simple and straightforward, yet properly reflect authentic results, the game feels even more "realistic" as a result, because players aren't breaking their immersion by flipping through charts and manuals.

This is why my philosophy of game design has always favored playability over "realism". If a game's not playable, it doesn't matter how "realistic" it can be. And playability and fun really go hand-in-hand, don't they? If you're not having fun playing a game, you're doing it wrong!

- HeadHunter

It’s a sliding scale and we all find our own setting depending on what we are looking for. No one setting is the correct one, I think we just look for opponents who are on a similar setting to our own.

DeleteI think you can get a fair amount of both, as long as the designers are willing to roll up their sleeves, do some tough work, and playtest the hell out of it. And then be willing to listen to player feedback and tweak when necessary.

DeleteI think the Lardies have done a fairly good job at making a game that reflects realistic outcomes without sacrificing playability. There is a bit more of a learning curve than a game like Bolt Action, but that's an acceptable cost to those players for whom some level of realism is important.

But if a game is super-realistic, yet unplayable... no one will play it. And then what does it matter? 8)